Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients

Chao Pui I1,3*, Cheng Gregory1, Zhang Lunqing2, Lo Iek Long3, Chan Hong Tou3, Cheong Tak Hong3

Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to compare the efficacies of gefitinib and erlotinib in treating EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.

Methods: 319 EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who had been treated with gefitinib or erlotinib at a Macau government hospital between 2005 Jan and 2015 Dec were retrospectively reviewed. Primary endpoint was overall survival (OS); progression-free survival (PFS) and disease control rate (DCR) were also analyzed.

Results: 259 patients were included in OS analysis. Nearly all patients were Asian (>99%). The median age in gefitinib group and erlotinib group were 62.5 and 60 respectively. Female patients predominated in gefitinib group (71.8% vs 46.6%, p<0.0001) and there was significantly more smokers or ever-smokers in erlotinib group (19.2% vs 35.0%, p=0.0046). Most patients were at a late stage of disease (stage III and IV ~85%) and >60% of patients received EGFR-TKI first-line. The median OS and PFS in gefitinib group and erlotinib group were 20.2 versus 26.3 months (p=0.0912) and 11.9 versus 13.4 months (p=0.0162) respectively, DCR was 72.1% versus 81.1 % (p=0.0799). Although erlotinib resulted in the better outcome, the difference was only significant with PFS. In the subgroup of patients receiving TKI first-line, erlotinib also showed a longer OS (19.2 vs. 34.6 months, p=0.0165).

Conclusion: For patients with EGFR mutations, gefitinib and erlotinib resulted in similar overall survival and disease control rate, but a significantly longer progression-free survival was observed with erlotinib. In patients receiving TKI as first-line therapy, erlotinib-treated patients also had a longer overall survival.

Introduction

In the last decade, the discovery of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and the development of various epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) had switched the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to a more precise direction. This change of practice is more significant among Asians where EGFR mutations were found to be more prevalent1-6. The most commonly found EGFR mutations are exon 19 deletions and exon 21 L858R substitutions7,8. After a series of randomized studies showing superior response rate and progression-free survival (PFS) in the treatment of NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations compared to chemotherapy9-13, EGFR-TKIs become a standard first-line treatment for patients with NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations now. Gefitinib and erlotinib are the first-generation TKIs that have been used for this indication since 2003 and 2004 respectively, providing the possibility of long-term response and survival studies. There were several head-to-head comparison studies between gefitinib and erlotinib, most of them did not show any significant survival and efficacy differences14-18. Only two studies in Taiwan show significantly better performance of erlotinib: erlotinib performed better than gefitinib in the study of Fan WC, et al. 2011 in which EGFR mutation status between the two treatment groups were unknown; and in EGFR wild-type patient group in the study of Wu WS, et al. 201219,20. Later, in a matched-pair case-control study from Lim SH, et al. 2014, there showed a favorable trend in PFS in gefitinib group compared to erlotinib group, though not reaching statistical significance (p=0.0056). However, most of the above studies composed of none or small proportion of first-line treated patients, which were not matched with the treatment recommendation of EGFR-TKIs in real-world setting. This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the difference in efficacy between gefitinib and erlotinib in Macau with EGFR-mutation NSCLC, with more than 60% of patients received gefitinib or erlotinib as first-line therapy.

Methods and materials

Patients

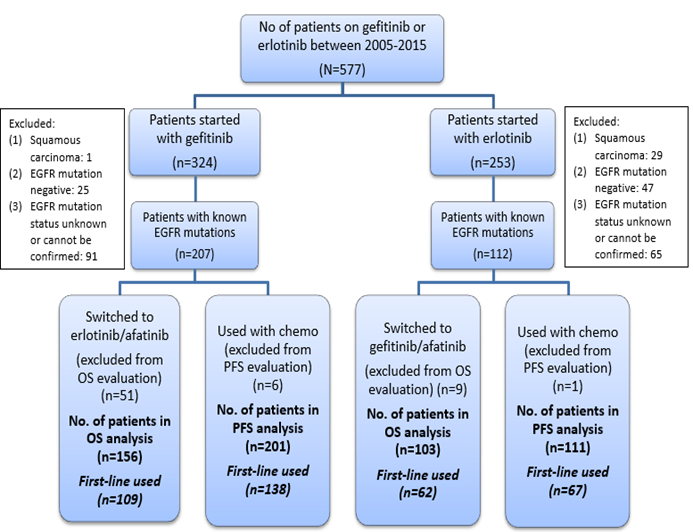

This study was approved by the ethic committee of Macau government hospital (Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário de Macau). 577 NSCLC patients who had been treated with gefitinib or erlotinib at Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário de Macau, between 2005 Jan and 2015 Dec were enrolled in this retrospective study. Medical charts, radiographic imaging and EGFR gene testing reports of the above patients were retrospectively reviewed. Clinical characteristics including: age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), stage of disease, smoking history, tumor histological type, metastasis, side effect profile, were recorded. Date of initial diagnosis, the date that EGFR-TKI treatment was commenced, date of documented disease progression and date of death or last follow-up were also recorded. Patients with squamous carcinoma (n=30), EGFR mutation-negative tumors (n=72), unknown EGFR mutation which could not be confirmed (n=156) were excluded. Gefitinib group was defined as patients who had received gefitinib as their first EGFR-TKI treatment and erlotinib group was defined as patients who had received erlotinib as their first EGFR-TKI treatment. Patients who had undergone surgery or radiotherapy were not excluded from this study. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Selection procedure of patients used in the study

Adapted from “Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” by Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Zhang Lunqing, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Efficacy evaluation

Patients were followed until 31st December, 2016 or the date of death. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and disease control rate (DCR) were secondary endpoints. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of EGFR-TKI treatment to the date of death from all causes. Patients still alive at the end of the follow-up period were censored at the date of their last follow-up visit. Patients who had switched to other EGFR-TKIs treatment during the follow-up period were excluded from the OS analysis (51 patients in gefitinib group and nine patients in erlotinib group). Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the time of EGFR-TKI treatment to the date of disease progression or death from all causes. Patients who remained alive and progression-free at the end of the follow-up period were censored at the date of their last disease assessment. Patients with radiographic imaging reports considered by physicians as partial response or stable disease, after at least eight weeks of EGFR-TKI treatment initiation, were defined as disease control. Treatment response evaluation was performed according to the latest version of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) group criteria valid at the assessment date. The EGFR mutation analysis was performed by nucleotide sequence analysis. Mutations in exons 18-21 were analyzed by PCR-direct sequencing. Patients who had concurrent chemotherapy during the EGFR-TKI treatment before disease progression were excluded from the PFS and DCR analysis. (6 patients in gefitinib group and one patient in erlotinib group) (Fig. 1)

Statistics

OS and PFS were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Disease control rates were compared using chi-square test. Cox regression analysis was used for univariate and multivariate analyses to identify significant prognostic factors for survival. Baseline characteristics were analyzed with chi-square tests. If the expected counts of any one of the cell were less than 5, Fisher’s exact tests were used. Tests were two-sided, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

319 NSCLC patients harbored with known EGFR mutations and had received gefitinib or erlotinib therapy at Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário de Macau, between 2005 Jan and 2015 Dec were identified. After exclusion of patients that had undergone switching EGFR-TKI therapy and concurrent chemotherapy, 259 patients and 312 patients were finally included in the OS analysis, PFS and DCR analysis respectively. Baseline characteristics of patients included in OS analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of patients harboured with known EGFR mutation and had received gefitinib or erlotinib therapy that were included in the OS analysis.

|

Gefitinib (all patients)(n=156) |

Erlotinib (all patients)(n=103) |

p | Gefitinib

(first-line) (n=109) |

Erlotinib

(first-line) (n=62) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethics | ||||||

| Asian | 155 (99.4%) | 102 (99.0%) | 1.0 | 108 (99.1%) | 61 (98.4%) | 1.0 |

| Age | ||||||

| Median (range) | 62.5 (33-89) | 60 (41-87) | 65 (37-89) | 64 (43-87) | ||

| ?65 | 66 (42.3%) | 38 (36.9%) | 0.3852 | 57 (52.3%) | 29 (46.8%) | 0.4890 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 44 (28.2%) | 55 (53.4%) | <0.0001 | 31 (28.4%) | 35 (56.5%) | 0.0003 |

| Female | 112 (71.8%) | 48 (46.6%) | 78 (71.6%) | 27 (43.5%) | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0-1 | 120 (76.9%) | 79 (76.7%) | 0.9667 | 76 (69.7%) | 45 (72.6%) | 0.6939 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Smoker or ever smoker | 30 (19.2%) | 36 (35.0%) | 0.0041 | 19 (17.4%) | 20 (32.3%) | 0.0268 |

| Stage of disease | ||||||

| III | 31 (19.9%) | 14 (13.6%) | 0.1570 | 17 (15.6%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.1115 |

| IV | 101 (64.7%) | 75 (72.8%) | 76 (69.7%) | 52 (83.9%) | ||

| Metastasis of disease | ||||||

| Bone | 45 (28.8%) | 27 (26.2%) | 0.6441 | 33 (30.3%) | 21 (33.9%) | 0.6278 |

| Brain | 13 (8.3%) | 20 (19.4%) | 0.0090 | 12 (11.0%) | 17 (27.4%) | 0.0061 |

| Pleural effusion | 52 (33.3%) | 38 (36.9%) | 0.5567 | 44 (40.4%) | 25 (40.3%) | 0.9955 |

| Line of treatment | ||||||

| First-line | 109 (69.9%) | 62 (60.2%) | 0.1082 | 109 (100.0%) | 62 (100.0%) | |

| Time interval from diagnosis to EGFR-TKI therapy, days | ||||||

| Median (range) | 71 (7-2537) | 78 (0-1805) | 40 (7-1563) | 36.5 (0-918) | ||

| >360 days | 21 (13.5%) | 16 (15.5%) | 0.6415 | 12 (11.0%) | 6 (9.7%) | 0.7856 |

| EGFR mutation type | ||||||

| Exon 19 | 91 (58.3%) | 46 (44.7%) | 0.0313 | 63 (57.8%) | 26 (41.9%) | 0.0466 |

| Exon 21 | 62 (39.7%) | 51 (49.5%) | 0.1214 | 44 (40.4%) | 35 (56.5%) | 0.0431 |

| T790M detected | 7 (4.5%) | 8 (7.8%) | 0.2697 | 4 (3.7%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0.8798 |

| Underwent treatment | ||||||

| Surgery | 40 (25.6%) | 29 (28.2%) | 0.6548 | 25 (22.9%) | 13 (21.0%) | 0.7667 |

| Radiotherapy | 69 (44.2%) | 50 (48.5%) | 0.4963 | 38 (34.9%) | 24 (38.7%) | 0.6159 |

| Reported side effect | ||||||

| Skin | 63 (40.4%) | 53 (51.5%) | 0.0801 | 42 (38.5%) | 33 (53.2%) | 0.0634 |

| GI | 30 (19.2%) | 10 (9.7%) | 0.0383 | 23 (21.1%) | 5 (8.1%) | 0.0272 |

Adapted from “Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” by Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Zhang Lunqing, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Nearly all patients in this study were Asian (>99%). The median age of patients in gefitinib group and erlotinib group were 62.5 and 60 respectively. There was a significantly larger proportion of female patient in gefitinib group (71.8% vs 46.6%, p<0.0001) and a significantly larger proportion of smoking or ever smoking patients in erlotinib group (19.2% vs 35.0%, p=0.0041). Most patients are at a late stage of disease (stage III & IV >85%) and more than 60% of patients received EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment. More patients in the erlotinib group had brain metastasis (19.4%, p=0.0090). About 90% of the studied patients bore exon 19 or exon 21 mutation and more patients in the gefitinib group harbored with exon 19 mutation, comparing to the erlotinib group (58.3% vs 44.7%, p=0.0313). The two groups were comparable with respect to other demographic and disease characteristics, and also the proportion of patients receiving EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment.

The proportion of patients in different demographic and disease characteristics group between gefitinib and erlotinib were also similar in the first-line treated patient subgroup, except that there were significantly more patients born exon 21 mutations in erlotinib group (40.4% vs 56.5%, p=0.0431) in the first-line treated patient subgroup. (Table 1)

Study population and Data collection and Processing

In the study period, a total of 6178 data of TB patients of all ages were retrieved from the data registry. Data variables collected included TB registration number, age, sex, type of TB disease and sputum smear results. Patients with incomplete data were excluded from the study. Treatment outcomes were recorded according to standardized National TB and Leprosy Control Program (NTLCP) classifications, based on WHO definitions6.

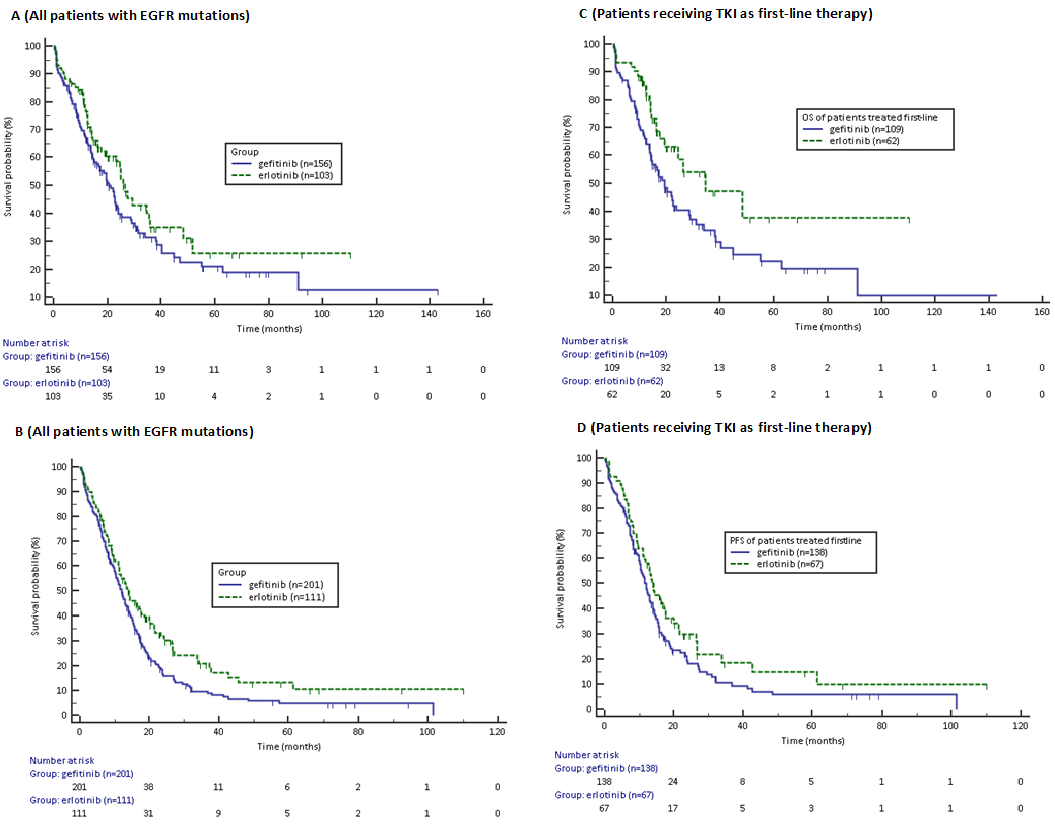

Overall survival

The median overall survival (OS) was 22.8 months in this study. There was no difference in OS between the 156 patients treated with gefitinib (censor, 58) and the 103 treated with erlotinib (censor, 54) (median OS, 20.2 vs 26.3 months; HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.04; p=0.0912) (Fig. 2). OS was significantly longer in the erlotinib group for patients receiving TKI first-line (median OS, 19.2 vs 34.6 months; HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37-0.87; p=0.0165) (Fig. 2). There was no statistically significant difference in OS between gefitinib and erlotinib in other subgroups including gender, age, performance status, smoking status and EGFR mutation types.

Figure 2: Overall survival (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) in patients with EGFR mutations receiving gefitinib or erlotinib. Overall survival (OS) (C) and progression-free survival (PFS) (D) in patients with EGFR mutations receiving gefitinib or erlotinib as first-line therapy. HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidential interval.

Adapted from “Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” by Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Zhang Lunqing, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Progression-free survival and disease control rate

The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 12.3 months in this study. PFS was significantly longer in the 111 patients treated with erlotinib (censor, 29) compared to the 210 patients treated with gefitinib (censor, 34) (median PFS, 11.9 months in gefitinib group vs 13.4 months in erlotinib group; HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.93; p=0.0162) (Fig. 2). The PFS in the exon 19 mutation subgroup were 12.9 months vs 21.3 months respectively for gefitinib and erlotinib (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.86; p=0.0075). No PFS difference was observed in the exon 21 mutation subgroup (median PFS, 10.2 months in gefitinib group vs 11.8 months in erlotinib group; HR, 0.79; 95%CI, 0.54-1.16; p=0.2420). PFS was also significantly longer in the erlotinib group in elderly (?65 years) (median PFS, 11.0 vs 24.3 months; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.38-0.88; p=0.0169), non-smoking patients (median PFS, 12.2 vs 14.3 months; HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96; p=0.0351), patients that started treatment within 360 days of diagnosis (median PFS, 11.3 vs 13.2 months; HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.95; p=0.0255) and patients with reported skin side effects (median PFS, 13.7 vs 21.5 months; HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.46-0.95; p=0.0306). There was no statistically significant difference in PFS between gefitinib and erlotinib in other subgroups including gender, performance status, and smokers. The disease control rate of gefitinib and erlotinib were 72.1% and 81.1% respectively, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.0799). Erlotinib was more effective in female patients (p=0.0200), never-smoker (p=0.0459) and patients that started treatment within 360 days of diagnosis (p=0.0499).

Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that presence of bone metastasis and pleural effusion and absence of skin side effect were independent risk factors associated with the poor OS. In univariate analysis, never-smokers and patients started treatment after 360 days of diagnosis seemed to have a longer OS. However, this effect was diminished in multivariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, erlotinib treatment, absence of pleural effusion, bone and brain metastases and EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment were associated with a longer OS. (Table 2) while gefitinib treatment, the presence of pleural effusion, bone and brain metastases, exon 21 mutation and absence of skin side effect were associated with a shorter PFS. (Table 3)

Table 2: OS in NSCLC patients treated with gefitinib and erlotinib according to clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Patient No (%)Total N= 259 | Median OS (95% CI) | Univariate p | Multivariate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | ||||

| TKI | |||||

| Gefitinib | 156 | 20.2 (15.73-23.73) | |||

| Erlotinib | 103 | 26.3 (23.00-35.73) | 0.0925 | 0.63 (0.43-0.92) | 0.0170 |

| Age | |||||

| <65 | 155 | 23.4 (19.33-31.50) | |||

| ?65 | 104 | 21.8 (14.40-26.27) | 0.3892 | 1.17 (0.81-1.70) | 0.4183 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 99 | 22.1 (15.73-26.27) | |||

| Female | 160 | 23.4 (19.33-30.13) | 0.4558 | 1.01 (0.65-1.56) | 0.9740 |

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0-1 | 199 | 23.0 (17.57-27.27) | 0.8843 | 0.98 (0.64-1.51) | 0.9370 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Smoker or ever smoker | 66 | 16.1 (12.33-24.60) | |||

| Never smoker | 193 | 24.5 (21.00-31.00) | 0.0382 | 1.33 (0.84-2.11) | 0.2272 |

| Stage of disease | |||||

| IV | 176 | 19.8 (16.07-23.87) | 0.1313 | 0.96 (0.62-1.50) | 0.8700 |

| Metastasis of disease | |||||

| Bone | 72 | 16.4 (11.23-23.00) | 0.0075 | 1.74 (1.13-2.66) | 0.0114 |

| Brain | 33 | 14.1 (12.43-34.63) | 0.1811 | 2.13 (1.26-3.60) | 0.0047 |

| Pleural effusion | 90 | 16.1 (12.43-21.83) | <0.0001 | 2.25 (1.52-3.31) | <0.0001 |

| Line of treatment | |||||

| First-line | 171 | 22.5 (17.57-33.87) | 0.3635 | 0.64 (0.43-0.96) | 0.0324 |

| Time interval from diagnosis to EGFR-TKI therapy, days | |||||

| ≤360 days | 222 | 21.8 (16.97-23.87) | |||

| >360 days | 37 | 51.5 (30.13-51.53) | 0.0076 | 0.53 (0.25-1.11) | 0.0928 |

| EGFR mutation type | |||||

| Exon 19 | 134 | 23.9 (19.80-31.00) | |||

| Exon 21 | 111 | 22.8 (14.43-31.50) | 0.5708 | 1.20 (0.83-1.74) | 0.3391 |

| Reported side effect | |||||

| Skin | 116 | 31.0 (23.87-46.97) | <0.0001 | 0.55 (0.38-0.79) | 0.0014 |

| GI | 40 | 29.0 (19.33-26.27) | 0.3930 | 1.03 (0.62-1.69) | 0.9131 |

Adapted from “Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” by Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Zhang Lunqing, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Table 3: PFS in NSCLC patients treated with gefitinib and erlotinib according to clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Patient No (%)Total N= 312 | Median PFS (95% CI) | Univariate p | Multivariate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | ||||

| TKI | |||||

| Gefitinib | 201 | 11.9 (10.20-13.73) | |||

| Erlotinib | 111 | 13.4 (11.07-18.43) | 0.0167 | 0.67 (0.50-0.89) | 0.0060 |

| Age | |||||

| <65 | 197 | 12.2 (10.83-14.00) | |||

| ?65 | 115 | 12.3 (9.53-15.63) | 0.5783 | 0.87 (0.65-1.17) | 0.3554 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 115 | 11.8 (9.80-14.23) | |||

| Female | 197 | 12.9 (10.67-14.43) | 0.4988 | 0.83 (0.60-1.14) | 0.2419 |

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0-1 | 245 | 11.9 (10.23-13.43) | 0.5588 | 1.21 (0.87-1.67) | 0.2565 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Smoker or ever smoker | 72 | 11.3 (8.93-14.93) | |||

| Never smoker | 240 | 12.9 (11.03-14.33) | 0.2891 | 1.02 (0.71-1.48) | 0.9002 |

| Stage of disease | |||||

| IV | 213 | 11.9 (10.43-14.00) | 0.2625 | 0.88 (0.62-1.25) | 0.4727 |

| Metastasis of disease | |||||

| Bone | 92 | 10.4 (8.13-12.90) | 0.0079 | 1.43 (1.05-1.96) | 0.0252 |

| Brain | 41 | 10.4 (6.63-12.43) | 0.0047 | 1.99 (1.35-2.95) | 0.0006 |

| Pleural effusion | 101 | 11.2 (8.03-13.17) | 0.0007 | 1.75 (1.30-2.37) | 0.0003 |

| Line of treatment | |||||

| First-line | 205 | 12.3 (10.83-14.00) | |||

| Not first-line | 107 | 12.4 (9.43-17.33) | 0.9516 | 0.86 (0.63-1.17) | 0.3320 |

| Time interval from diagnosis to EGFR-TKI therapy, days | |||||

| ≤360 days | 270 | 11.8 (10.23-13.73) | |||

| >360 days | 42 | 18.5 (12.30-32.13) | 0.0141 | 0.72 (0.44-1.16) | 0.1756 |

| EGFR mutation type | |||||

| Exon 19 | 160 | 14.3 (11.93-16.33) | |||

| Exon 21 | 136 | 11.2 (9.10-12.83) | 0.0440 | 1.32 (1.01-1.74) | 0.0428 |

| Reported side effect | |||||

| Skin | 148 | 15.7 (12.90-20.00) | <0.0001 | 0.56 (0.42-0.74) | <0.0001 |

| GI | 55 | 14.9 (9.80-19.80) | 0.2376 | 0.95 (0.67-1.35) | 0.7746 |

Adapted from “Retrospective analysis of Gefitinib and Erlotinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” by Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Zhang Lunqing, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Discussion

Gefitinib and erlotinib had been used in Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário de Macau for the treatment of NSCLC since 2005, especially in NSCLC patients harbored with EGFR mutations. This retrospective study compared the effectiveness of gefitinib and erlotinib, in treatment NSCLC patients with EGFR-mutations. Since various studies have shown the strong association between EGFR mutation and treatment effect of EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC treatment, only patients with known EGFR mutations were included in this study.

The overall survival between gefitinib and erlotinib in this study were 20.2 months and 26.3 months respectively (p=0.0912). A favorable trend of longer survival was observed in erlotinib group, however, the difference between two treatment groups did not reach any statistical significance. Generally, in oncology studies, OS is considered the strongest endpoint. However, the effect of post-progression therapy and crossover treatment always masked the possible difference in survival between treatments. In order to minimize the confounding effect of crossover treatment, samples that had switched to other EGFR-TKIs were all excluded. However, the influence of post-progression therapy, esp. second- or third-line chemotherapy, on overall survival was still in effect. In the subgroup analysis, survival differences favoring erlotinib were seen in patients using EGFR-TKI first-line (p=0.0165). No difference was found between gefitinib treatment group and erlotinib treatment group in both exon 19 mutation subgroup and exon 21 mutation subgroup.

In order to further evaluate the effectiveness between gefitinib and erlotinib, this study also analysis the PFS between these two groups. Results showed significantly longer PFS in erlotinib group (p=0.0162). This superiority of performance in erlotinib treatment group was also seen in the subgroup of elderly patients, never-smokers and in patients harboring exon 19 mutation, in patients with reported skin side effect and in patients that started treatment within 360 days of diagnosis.

This was the first known head-to-head comparison study showing significant differences in efficacies between gefitinib and erlotinib when used in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients. Patients in erlotinib treatment group showed significantly longer OS during first-line treatment, and also a significantly longer PFS, particularly in exon 19 mutation subgroup. Although baseline characteristics such as sex, smoking status and proportion of patients with brain metastases were not well balanced, they all favored the gefitinib arm according to published evidence and possibly not accounted for the superiority in performance of erlotinib in this study. Other similar studies14-20 either show no difference between gefitinib and erlotinib, or they show non-significant favorable trend for gefitinib. One possible explanation of the difference was most of these studies consisted of very few first-line EGFR-TKI treated EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients. In conclusion, there was no significant difference in overall survival and disease control rate between gefitinib and erlotinib in the treatment of NSCLC in EGFR-mutated patients. However, erlotinib may result in a longer PFS, particularly in patients with exon 19 mutation and a longer OS when used as first-line treatment.

However, this retrospective study had several limitations. Although patients that had undergone switching EGFR-TKI therapy had been excluded from the OS analysis in order to minimize the confounding effect of post-progression therapy by second EGFR-TKI, the effect of survival by post-progression chemotherapy could not be prevented, which may affect the OS. This may be one of the reasons why no significant overall survival difference was shown in this study. Moreover, baseline characteristics were not well balanced between the two groups, there were significantly more male patients, smoking patients and more patients with brain metastases in the erlotinib treatment group, all were considered as factors associated with poor prognosis. Also, this study was retrospective, non-randomized in nature and was a single-institution study. Finally, this study did not consider clinical factors such as dose intensity, treatment compliance, or quality of life. Patietns with exon 19 mutations seemed to have better PFS with erlotinib but further investigation through well-controlled trials is needed to confirm whether erlotinib was superior than gefitinib in overall survival and clarify the characteristics of patients who would benefit most from erlotinib treatment.

Acknowledgement:

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest:

This research does not have any conflict of interest to declare.

List of abbreviations used:

NSCLC: non-small-cell lung cancer

EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor

EGFR-TKI: epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

OS: overall survival

PFS: progression-free survival

DCR: disease control rate

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

PS: performance status

RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

HR: hazard ratio

CI: confidential interval

Authors’ contributions:

Conception or design of the work: Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory

Data collection: Chao Pui I, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Data analysis and interpretation: Chao Pui I

Drafting the article: Chao Pui I

Critical revision of the article: Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

Final approval of the version to be published: Chao Pui I, Cheng Gregory, Lo Iek Long, Chan Hong Tou, Cheong Tak Hong

References

- Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 2005; 97(5): 339–46.

- Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004; 304(5676): 1497–500.

- Shigematsu H, Gazdar AF. Somatic mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway in lung cancers. Int. J. Cancer. 2006; 118(2): 257-62.

- Bell DW, Brannigan BW, Matsuo K, et al. Increased prevalence of EGFR-mutant lung cancer in women and in East Asian populations: analysis of estrogen-related polymorphisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008; 14(13): 4079–84.

- Keedy VL, Temin S, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation testing for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer considering first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011; 29(15): 2121–7.

- Chou TY, Chiu CH, Li LH, et al. Mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor is a predictive and prognostic factor for gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005; 11(10): 3750-7.

- Ladanyi M, Pao W. Lung adenocarcinoma: guiding EGFR-targeted therapy and beyond. Mod. Pathol. 2008; 21(suppl 2): S16–22.

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004; 350(21): 2129–39.

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009; 361(10): 947–57.

- Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. North-East Japan Study Group. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010; 362(25): 2380–8.

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. West Japan Oncology Group. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11(2): 121–8.

- Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011; 12(8): 735-42.

- Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Spanish Lung Cancer Group in collaboration with Groupe Français de Pneumo-Cancérologie and Associazione Italiana Oncologia Toracica. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13(3): 239–46.

- Kim ST, Lee J, Kim JH, et al. Comparison of gefitinib versus erlotinib in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer who failed previous chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010; 116(12): 3025-33.

- Wu JY, Wu SG, Yang CH, et al. Comparison of gefitinib and erlotinib in advanced NSCLC and the effect of EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer. 2011; 72(2): 205-12.

- Kim ST, Uhm JE, Lee J, et al. Randomized phase II study of gefitinib versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer who failed previous chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2012; 75(1): 82–8.

- Lim SH, Lee JY, Sun JM, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes following gefitinib and erlotinib treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer patients harboring an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in either exon 19 or 21. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014; 9(4): 506–11.

- Urata Y, Katakami N, Morita S, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing gefitinib with erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced lung adenocarcinoma: WJOG 5108L. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016; 34(27): 3248-57.

- Wu WS, Chen YM, Tsai CM, et al. Erlotinib has better efficacy than gefitinib in adenocarcinoma patients without EGFR-activating mutations, but similar efficacy in patients with EGFR-activating mutations. Exp. Ther. Med. 2012; 3(2): 207-213.

- Fan WC, Yu CJ, Tsai CM, et al. Different efficacies of erlotinib and gefitinib in taiwanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011; 6(1): 148-55.