Vaping-associated lung injury: a case report and literature review

Dewansh Goel, MD, MPH*, Kenneth Iyamu, MD, FACP

University of Central Florida/HCA GME Consortium, Ocala Regional Medical Center, Florida, USA

Abstract

Usage of vaping and electronic cigarettes products is a growing trend among young adults, with rising rates worldwide. Such products are gaining popularity for many reasons including an alternative to smoking cigarettes, trying something new, or as a means to relax. While users may feel that these products are less harmful or a safer substitute to smoking traditional products, the side effect profile of vape inhalation has the potential for profound injury to the lung tissue and significant respiratory failure. We would like to present a case in which a young male who was evaluated at our Emergency department for acute onset respiratory failure subsequently requiring invasive mechanical ventilation in the setting of vaping associated lung injury (VALI). In the case report, we will highlight the patient’s clinical course as well as a summary of the current evidence surrounding evaluation, diagnosis and management of this emerging pathology. We want to emphasize the importance of a detailed history which should include the use of vaping products when a young patient presents with acute respiratory failure, allowing VALI to be in the differential diagnosis. Additionally, we want to compare the clinical presentation of VALI to that of COVID-19 pneumonia as they both have many similar attributes including symptoms and findings on lung imaging studies.

Background

Recently, there has been a shift among young adults and teens to use electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and vaping products compared to traditional cigarettes with nearly a nine fold increase among high schoolers and six fold among middle school students between 2001 and 20141. The alarming increase seems to stem around one or more of the following self-reported motives; e-cigarettes and vaping products are less harmful compared to traditional cigarettes, they are useful as a bridge to smoking cessation, as methods to relax/cope with anxiety/depression or even just try something new1. Whatever the objective is behind using modern day vape products, the rise in usage presents a significant public health burden as well as a clinical challenge when patients present with acute respiratory failure secondary to vaping-associated lung injury (VALI). Vape products work by aerosolizing a solvent that contains various flavors and nicotine. The aerosol is then vaped, leading to peak serum nicotine content in the body within five minutes2. Contents of the liquid include carcinogens such as formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, with additional toxins that have limited documented studies on adverse effects in humans. The amount of inhaled toxins depends on various factors including flavors, the actual device, and the voltage the e-cigarette is set at2.

There have been more than 2500 cases of hospitalized patients due to (VALI) as of December 2019 with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC being informed of 2400 cases and approximately 50 cases of death3. Of the 2400 cases that were reported to the CDC, 2.7% of the patients discharged required readmission within an average of four days. The growing number of cases between August 2019 and December 2019 was alarming, resulting in the creation of Vaping Associated Pulmonary Illness Task Force to collect surveillance data and perform epidemiologic evaluation on VALI4. We want to share a case of a young adult who presented to our emergency room (ER) in respiratory failure requiring intensive care unit management secondary to VALI.

Case Presentation

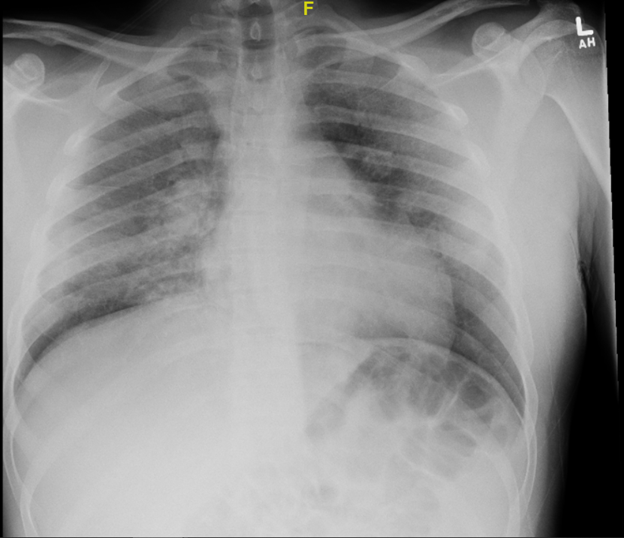

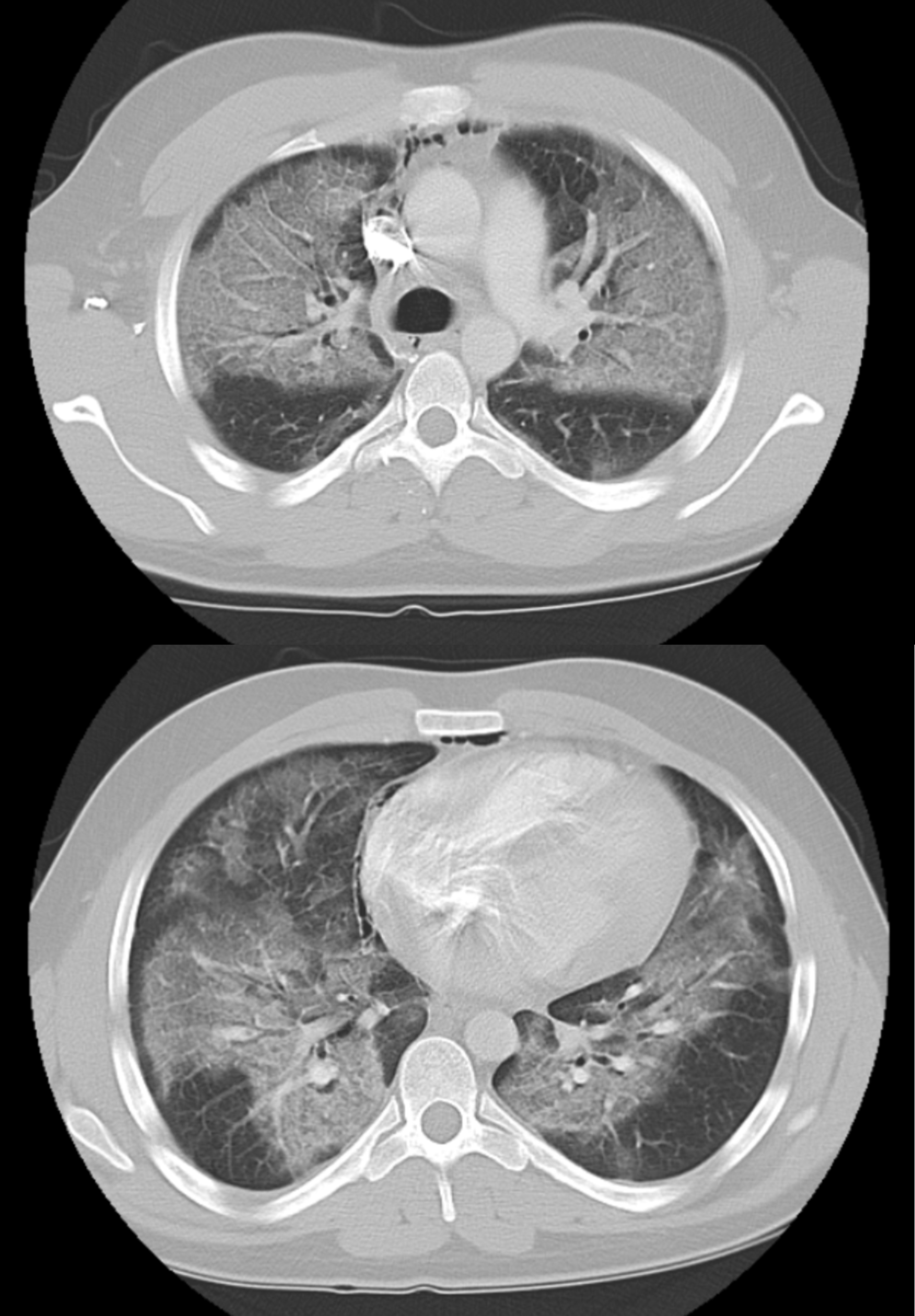

Here is a 24 year old male with past medical history of meningitis at age 15 and marijuana use (both smoking and vaping forms), who presented to our ER with cough, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting in the setting of his mother recently being sick with flu like symptoms. Patient previously visited an urgent care for similar symptoms and was sent home with supportive treatment and oseltamivir. Over the next few days, his symptoms did not improve and he presented at our ER at which time he was also sent home with supportive care for suspected viral gastroenteritis after a negative influenza test. The next day, he returned to our ER, with worsening shortness of breath, subjective fevers, night sweats, body aches, and pleuritic chest pain. Pertinent physical exam findings included temporal temperature of 36.8°C, tachycardia of 110 beats/min, respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min, blood pressure of 123/81 mm/hg and oxygen saturation of 95% on 4 liters/min nasal cannula (Pa02/FIO2 ratio 78). Significant laboratory findings were leukocytosis of 14000 cells/cc with otherwise normal complete blood count and metabolic panel. Pertinent imaging findings on chest x-ray were that of bilateral peri-hilar infiltrates (Figure 1) followed by chest CT scan with contrast notable for bilateral air space opacities suggestive of multifocal pneumonia with differential diagnosis of pulmonary edema and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Figure 2A & 2B). In view of the laboratory findings, image findings, and clinical exam indicating a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with possible source indicating sepsis, patient received a dose of vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, metronidazole and methylprednisolone 125mg in the ER and was admitted to internal medicine (IM) general ward for further evaluation and management.

Figure 1: Admission Chest X-ray showing bilateral peri-hilar opacities

Figure 2A & 2B: Chest CT scan with contrast: Lung segments showing diffuse bilateral air space opacities suggestive of pulmonary edema vs ARDS. Upper lobes (top figure) | Lower lobes (bottom figure)

Upon prompt evaluation by IM team, patient was noted to have tachypnea to 24-30 breaths/min, oxygen saturation ranging 90% to 92% on 4 liters/min nasal cannula, and appeared to be in severe respiratory distress with labored breathing and inability to complete his sentences. He was switched to a non-rebreather oxygen delivery mask, started on parenteral ceftriaxone, doxycycline, and bronchodilator treatments. Arterial blood gas on admission showed a pH of 7.4 with a PO2 of 78 mmHg, HCO3 of 22 mmol/L, PCO2 37 mmHg and subsequent blood gas (4 hours later) showed a pH of 7.47, PO2 of 56 mmHg, HCO3 of 22 mmol/L and PCO2 30.9 mmHg while on the non-rebreather mask. Noting the worsening hypoxia and increased work of breathing, decision was made to consult critical care and transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer monitoring.

Later that day in the ICU, patient became increasingly diaphoretic, pale and mildly cyanotic, pulse oximetry showed < 50% saturation, tachycardia and elevated blood pressures with frothy sputum production. Patient was sedated with midazolam and fentanyl and emergently intubated. An infectious disease specialist was consulted and empiric Trimethoprim / Sulfamethoxazole for possible Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia (PCP) was added in the setting of CT chest findings. During the ICU course, laboratory testing including Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae, HIV and hepatitis were negative as were blood cultures. Bronchoscopy was performed as a both diagnostic and therapeutic procedure to look for any structural abnormality and to sample cells directly from the airway, trying to isolate a microorganism or identify a cellular process by looking at the cells under a microscope. Results of bronchoscopy performed while the patient remained intubated by the intensivist with assistance from respiratory therapist in the ICU were negative for gram stain and did not isolate any organism including PCP. On ICU day three, Trimethoprim / Sulfamethoxazole was discontinued and on day four, patient was extubated. On ICU day six, patient was downgraded from ICU to IM wards and subsequently discharged to home two days later with a prepackaged tapering 4mg Methylprednisolone prescription and no additional antibiotics per recommendations from infectious disease specialist.

Discussion

For any patient presenting with respiratory symptoms, the objective data points including radiographic imaging have to be correlated with a detailed history since the clinical presentation associated with respiratory failure is often nonspecific and multifactorial. Our patient presented to us in Dec of 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic began to surface. It is important to note that if our patient had a similar clinical presentation and radiographic findings closer to March/April of 2020, COVID-19 viral infection would have been on the differential diagnosis and evaluation for the same would have been warranted. The chest CT findings for COVID-19 infection vary, but include any combination of multilobar, bilateral ground glass opacities or consolidation. Equally, radiology images that depict septal thickening, pleural thickening, bronchiectasis or subpleural involvement, are also associated with COVID-19, but are nonspecific and similar to findings seen with vaping associated lung injury5,6.

Vaping induced lung injury shows a rising trend across the globe since early 2019, however the pathology is still poorly understood. One study that looked at biopsy specimens from patients with confirmed or suspected VALI found that all specimens were positive for acute lung injury, fibrinous pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar damage and organizing pneumonia7. In majority of VALI cases, respiratory specimens are not sent for histopathologic analysis. Diagnosis is centered on the clinical picture of a young adult who presents with respiratory distress, cough, and chest pain in the setting of vaping history with CT chest images of basilar consolidation with ground glass opacities. In addition to similar objective findings, both pathologies mimic each other with clinical features including fever, cough, shortness of breath and non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms6,8,9.

Although direct cause- effect is not yet established, the typical presentation of such a case suggests a possible link and the need to spread awareness of the potential severity of VALI10. The evaluation should include a good clinical history including questions surrounding the use of tobacco products as well as modern day vaping products. Additional investigation for suspected cases should include imaging of the chest starting with a chest x ray followed by chest CT scan. Hospital admission should be considered for those with respiratory distress or with hypoxia and include empiric antibiotics and steroids8. Given the histopathologic findings suggestive of an inflammatory process, the use of steroids can be helpful for both inflammation reduction as well as symptom relief for the patient. On the same note, empiric antibiotics are initially considered due the overlapping and acute presentations of community acquired pneumonia with that of VALI and can be des-escalated as negative cultures are resulted. Pulmonology specialist consultation and evaluation is another aspect of medical management that can be useful for possible bronchoscopy to narrow down the etiology of the acute pulmonic process. Upon discharge, patient should receive education on behavioral counseling and the importance on discontinuing vaping and nicotine containing products8.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

Funding

Present work was performed without any direct or indirect financial support. There are no funding sources to be disclosed.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors reported any conflict of interest directly or indirectly connected with this manuscript. There are no conflicts of interest to disclose regarding the production, submission or publication of this case report.

References

- Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, et al. Self-Reported Reasons for Vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th Graders in the US: Nationally-Representative Results. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016; 165: 275-8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.017

- Dinakar C, O'Connor GT. The Health Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016; 375(14): 1372-1381. doi:10.1056/nejmra1502466

- Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, Patel MT, et al. Syndromic Surveillance for E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382(8): 766-772. doi:10.1056/nejmsr1915313

- Mikosz CA, Danielson M, Anderson KN, et al. Characteristics of Patients Experiencing Rehospitalization or Death After Hospital Discharge in a Nationwide Outbreak of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 68: 1183-1188. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm685152e1

- Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020; 215(1): 87-93. doi:10.2214/ajr.20.23034

- Henry TS, Kanne JP, Kligerman SJ. Imaging of Vaping-Associated Lung Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019; 381(15): 1486-1487. doi:10.1056/nejmc1911995

- Butt YM, Smith ML, Tazelaar HD, et al. Pathology of Vaping-Associated Lung Injury. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019; 381(18): 1780-1781. doi:10.1056/nejmc1913069

- Christiani DC. Vaping-Induced Acute Lung Injury. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382(10): 960-962. doi:10.1056/nejme1912032

- Darmawan Do, Gwal K, Goudy BD, et al. Vaping in today’s pandemic: E-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury mimicking COVID-19 in teenagers presenting with respiratory distress. Sage Open Medical Case Reports. 2020; 8: 2050313X20969590. doi:10.1177/2050313X20969590

- Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Evaluating and Caring for Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use Associated Lung Injury - United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68: 919-927. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6841e3